My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

These are supposedly the last words famously attributed to Jesus on the cross which is found only in Matthew and Mark gospels. I normally see this passage a highly problematic in relation to salvation by the death on cross as it appears by this saying an abandonment of Jesus by God the Father. Why should Jesus have thought himself as being abandoned from God at the very moment when, according to christian theology, he was fulfilling God’s plan? Maybe I will talk about this matter for future post because this time I want to talk about this passage in the light of the hebrew and aramaic use of the passage.

For me this words of Jesus is really interesting, as this one of very rare place in the greek gospels which preserve the original language of Jesus allegedly quoted straight from the mouth of Jesus in the Gospels in Matthew 27:46, usually appear in Roman transliteration as:

Eli Eli lama sabachthani

NB: Mark 15:34 uses eloi instead of eli and this surely is an interesting discrepancy which I will talk about in future post

Christians have argued that this quotation turns out, is quoted from Psalm 22:2, which in Hebrew Bible it reads:

Eli Eli lamma azabtani אֵלִ֣י אֵ֭לִי לָמָ֣ה עֲזַבְתָּ֑נִי

Tehillim – Psalms – Chapter 22

Fine, now wait a minute, that “Eli Eli lama sabachthani ” is it an Aramaic or Hebrew expression? which language Jesus uses here?

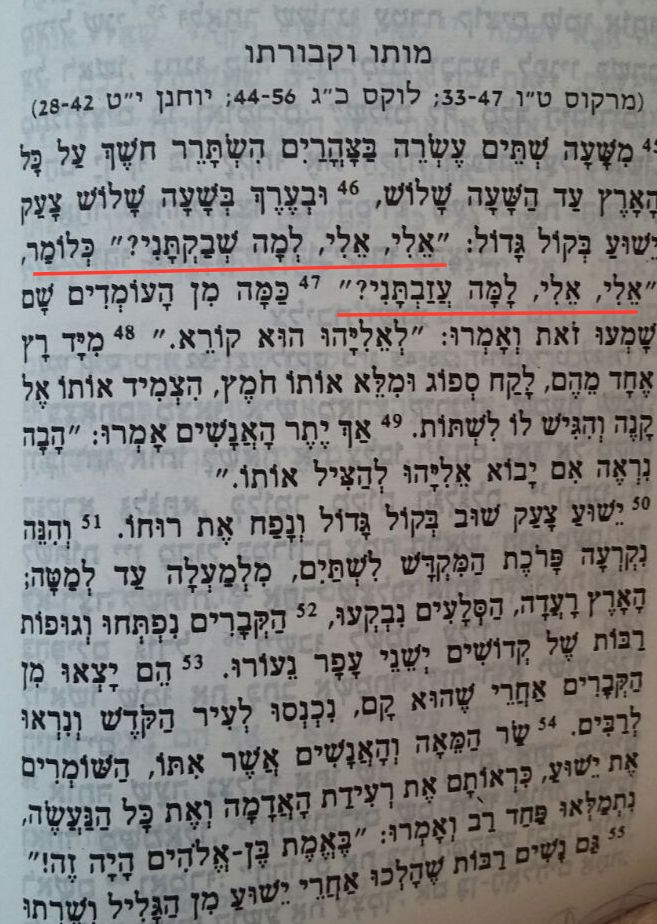

Let’s check the Hebrew Translation of Matthew 27:46 (from the 1976 United Bible Society, ha Berit ha-Chadashah הברית החדשה)

הברית החדשה על-פי מיתי 27:46

There it says:

Eli Eli lema shebaqtani א ִלי ֵא ִלי ְלְמָה ְשַׁב ְקָתִּני Kelomar כּלומר (“which means”) Eli Eli lamma azabtani אֵלִ֣י אֵ֭לִי לָמָ֣ה עֲזַבְתָּ֑נִ

Therefore it implies that “Eli Eli lema shebaqtani” is not an Hebrew words but rather a non-hebrew words which mean “Eli Eli lamma azabtani” in Hebrew.

So if it is not Hebrew, the question what language is “Eli Eli lema shebaqtani” / “Eli Eli lama sabachthani ” expression? We naturally assume that it is an Aramaic expression or is it?. Then one must ask if this quotation really was quoted from book of Psalms 22:2, which book Psalms is it which has this expression? We are left for just two options for the origin of this expression: whether (1) Jesus quoted Masoretic Hebrew text or (2) the Aramaic Targums.

- If Jesus did quote this expression from Masoretic Hebrew text, is it Ben Asher or Ben Nafthali version? I am interested if any christian can show us the expression “Eli Eli lema shebaqtani” in there.

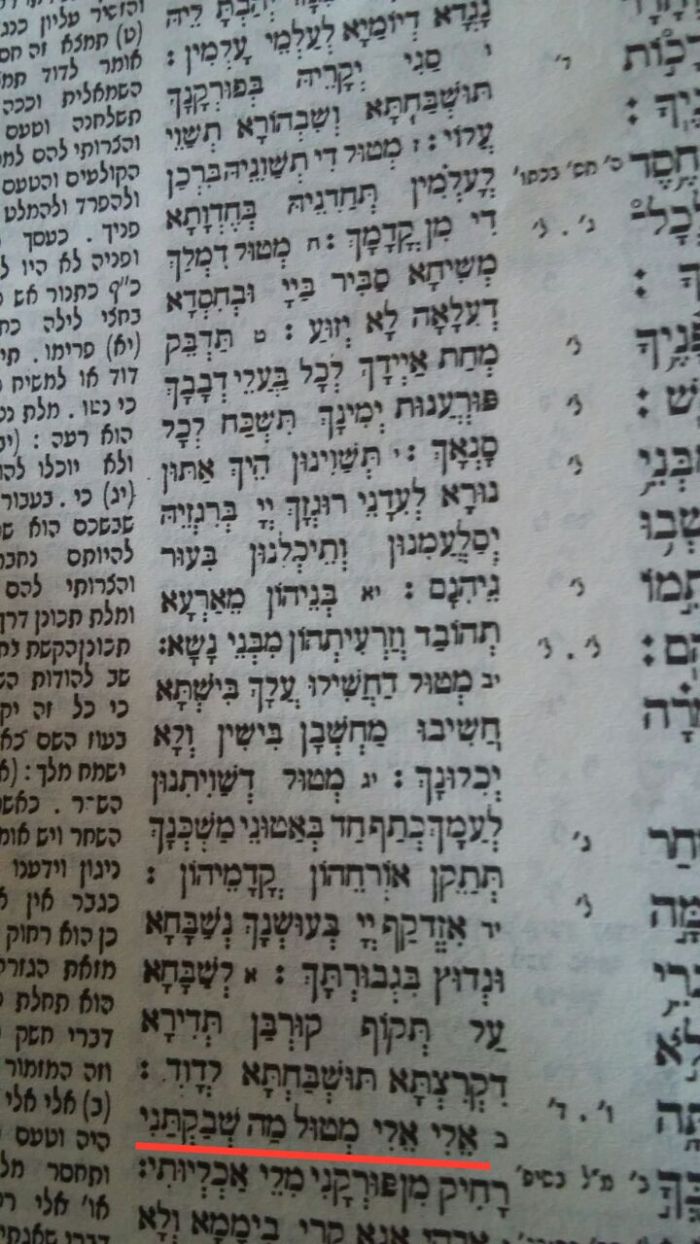

- If Jesus meant to quote Aramaic Targums. is it Targum Onqelos, or Targum Yonathan or Targum Yerushalmi or Targum Neofiti? which one is it which say “Lema shebaqtani”. I doubt that there is such expression because Aramaic Targums do not say “Lema shebaqtani“א ִלי ֵא ִלי ְלָמָ֣ה ְשַׁב ְקָתִּני but instead “Eli Eli Methul ma shebaqthani” א ִלי ֵא ִלי ְמטוּל ַמה ְשַׁב ְקָתִּני although this Aramaic Targumic expression use a more correct root š-b-q ש ב ק in their translations of the Psalm 22, the Aramaic word used sabachtani which is used in most of Bible translation is based on the verb sebach/šebaq, ‘to allow, to permit, to forgive, and to forsake’, (please refer to the figure below). Interestingly enough “Eli Eli lama sabachthani ” really is a mix hebrew and Aramaic words.

Targum Jonathan Tehilim 22:2

Now since non of these two options do not have verbatim expression of “Eli Eli lama sabachthani” we are in a dilemma understanding what is going on, which Psalm 22 source then did Jesus quote this Aramaic expression from? Clearly Jesus is not quoting the canonical Hebrew Bible version (Eli Eli lamma azabtani) and but why then did Jesus mix Hebrew and Aramaic expression not found in known Aramaic Targum?

Does it turns out to be a case where Jesus actually refer to specific Targumic source no longer exist? or is it a case where jewish scribe did in fact changed the Aramaic Targums such is in the Targum Jonathan I just provide? Or I will argue that this expression may well be a case that whoever wrote the gospel of Matthew misquote the book of Psalms.

God Knows Best.

Categories: Bible

Salaam Eric,

Interesting post. What are the differences in meaning and theological implications in regard to Shebaqtani/Sabbachthani vs. Azabtani? Also what is the meaning of “Methul Ma”?

LikeLike

I think we need more clarification. Is this just a simple misquote, or something of more importance which affects the meaning of the verses in question. It seems to me that there may be some theological implications in regard to the meaning of the text based on which word is used. Why would Martin Luther choose to link to Psalm 22:2 and use the Hebrew word Asabthani/Asavthani rather than the Aramaic Shebaqtani/Sabachthani? As far as I can tell there is minimal difference, “left or leave me” vs. “forsaken me” either word indicates abandonment.

Also if it is a case of the pseudepigraphal author of Mark misquoting Psalms, then we can’t really know if Jesus really spoke these words at all anyway. It is just the author writing something that he may have thought implied some deeper meaning, rather than an actual direct quote from Jesus himself. But, if somehow, it can be confirmed that Jesus actually said these words either in Hebrew or Aramaic, I would interpret it as meaning that he is indeed expressing despair that God had abandoned him, allowing him to be crucified rather than to complete his original mission which, if only to summarize, was to communicate the message of Islam.

LikeLike

Greetings Ibn Issam

I know these questions were not posed to me, but I hope I will be forgiven for commenting, as I am familiar with some of what was covered.

Ibn Issam wrote

{{What are the differences in meaning and theological implications in regard to Shebaqtani/Sabbachthani vs. Azabtani?}}

Their semantic ranges overlap. The former appears as the translation of the latter in various sources (e.g. Targum Yonatan, the Peshitta, et cetera).

Ibn Issam wrote

{{what is the meaning of “Methul Ma”?}}

Literally “because of [or on account of] what”. It is used in the sense of “why?”

Ibn Issam wrote

{{Is this just a simple misquote, or something of more importance which affects the meaning of the verses in question.}}

I would say neither. Christ was not misquoting the text. Rather He employed a version of the verse which does not line up perfectly with the wording in either the Masoretic Text or Targum Yonatan (though the meanings are the same).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dennis,

Thanks for your comments in answer to my questions. Although I would like to believe it, I am still not absolutely convinced that these are the actual words of Jesus rather than those of the unknown author. I would be more convinced if the verse appeared in the Q Gospel, but since there is no similar verse in Luke, I think that must preclude the possibility.

LikeLike

With the Name of Allah

Wa Salam akh ibn Issam,

I admit there could be several issues around this notable differences of Jesus sayings which I should addressed, to my disappointment many scholars have glossed over this utterance as Aramaic without even really bother to verify and give reason if it indeed is.

Methul Ma מטוּל מה conforms with correct vernacular Aramaic and correspond to the word Lama למה in Hebrew which means “why” as in arabic Limādzā لماذا . But still those are different languages.

Take a look at the following table:

אלי אלי למה עזבתני

אליאלי מטול מה שבקתני

ܐܠܝ ܐܠܝ ܠܡܢܐ ܫܒܩܬܢܝ

Notice that none of the aforementioned expression is exactly the same. While these could be close in meaning, they are significantly different to merit investigation what the exact expression of Jesus, and why is the difference.

The fact is the expression appear to be a mixed Aramaic and hebrew rather than commonly understood as Aramaic because of the root verb š-b-q שבק “abandon”, which is originally Aramaic. While correct Biblical Hebrew counterpart to this word ‘-z-b עזב. Thus, Jesus definitely is not quoting the canonical Hebrew version of Psalms of David as christians love to argue. As for the implications I propose that it could be an evidence where jewish scribe did in fact changed the text of Hebrew Bible or that whoever wrote the gospel of Matthew misquote the book of Psalms due to their infallibility. Other possibility is plausible of course that Jesus did not mean to quote Psalms rather Jesus really have thought himself as being abandoned from God , and asked for his help. We know from the Qur’an that he was indeed saved by God.

LikeLike

In Arabic , ( Why ) is لِمٓ Lima

Limatha = tow words (Lima ) + ( Tha) , yet they became one word. Tha = this .

It’s sort of ( Why this)

LikeLike

Walter G. Clippinger writes in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia that, “The spirit revealed by Jesus in this utterance seems to be very much like that displayed in the Garden when He cried out to have the cup removed from Him.” http://biblehub.com/topical/e/eloi.htm

So whether he, or the author, was speaking/writing in Aramaic, Hebrew or a mixture of both, the meaning is very close and similar and the statement in question seems to be a genuine expression of regret at being abandoned by God in his final moments (as Yahya Snow mentioned). Other than wishful thinking on the part of some, there is nothing solid to indicate that it is a direct or indirect quote of Psalms, which might have indicated a link with a Davidic Messiah. If David Giron wishes to argue that it is not a misquote, that is fine, but as Clippinger indicates, we should look at the spirit in which Jesus is purported to have uttered these words – Clearly, Jesus did not wish to be crucified as it was never part of his original aim or purpose.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Greetings Ibn Issam

Ibn Issam wrote:

{{I am still not absolutely convinced that these are the actual words of Jesus rather than those of the unknown author. I would be more convinced if the verse appeared in the Q Gospel}}

To be fair, however, doesn’t your own faith move you to the position that a statement not appearing in the hypothetical Q-source tells us little about whether Christ actually uttered it? I ask because does the Qur’an attributes statements to Jesus which proponents of the Q-hypothesis would say do not appear in that hypothetical source.

Ibn Issam wrote:

{{the meaning is very close and similar and the statement in question seems to be a genuine expression of regret at being abandoned by God}}

That seems to me hard to demonstrate either way (and the conclusions we reach may well depend on the lens through which we view the statement). For what it’s worth, the statement comes off as a fine Aramaic translation of the opening of the 22nd Psalm (which just so happens to be a Psalm that some Jews interpreted as alluding to a Messianic figure suffering on behalf of others). While His precise intention cannot be proven either way, the very real possibility that He was deliberately alluding to that Psalm to hint that more is to come remains.

Ibn Issam wrote:

{{there is nothing solid to indicate that it is a direct or indirect quote of Psalms}}

Save for the fact that it reads like a straight Aramaic translation of Psalm 22:1.

LikeLike

With the Name of Allah

Hi Denis, Thanks for your comment.

I apologise I must be very quick so I will touch some of your point briefly

//However, if you’re asking if Psalm 22 refers to the death of the Messiah, I would say no (at least not in any explicit or obvious way)//

Yes, because you are the one who initially brought the “messianic” argument of Psalm 22. I did not mean the greek testament.

//No, nor does it claim He will be born of a virgin, but I don’t think there is any requirment for all of the faith to be stated in the 22nd Psalm.//

Born a virgin is not part of trinitarian formulation the Qur’an condemns. Even if it is not in the hebrew bible this does not compromise monotheism. The central faith of trinitarianism the Messiah who is also God and then died to atone for people sin.

//Is there any Aramaic version of the Psalms which predates Christ? I do not think there is.//

Neither scholarships have good evidence that aramaic targumim predates ‘Eesa Almasih. Even it does this is still problematic as nowhere then the Matthew expression match with any written evidences of Psalm 22.

//The statement in Matthew reads as a fine Aramaic translation of the opening of that Psalm, and I see no requirement for it match other Aramaic translations//

I beg to differ, how can anyone can conclusively claim that it is the correct Aramaic expression while none of the supposedly Jesus quoting Psalm expression is exactly the same with each other whether it’s in Masoretic, Aramaic targumim and Syriac NT, (here I include Markan text )

אלי אלי למה עזבתני

אליאלי מטול מה שבקתני

ܐܠܗܝ ܐܠܗܝ ܠܡܢܐ ܫܒܩܬܢܝ

ܐܠܝ ܐܠܝ ܠܡܢܐ ܫܒܩܬܢܝ

Regarding the scholars on the dating of Yonathan I am well aware of discourse, my understanding what those scholars meant by the possible dating is the complete collection of the text itself but their literary origin goes back to Eastern Aramaic Babylonian style which origin undoubtedly pre-dating Christ. Perhaps I will delve into this matter more InshaAllah elaborate later if needed but this is not an important point, you are the one who make claim that Yonathan is post dating Christ, as if it is a settled case. I point out that this is not. You still can not deal with the fact that was none of the supposedly Jesus quoting Psalm expression is exactly the same with each other whether it’s in Masoretic, or Aramaic targumim or even Syriac sources. This is a serious problem with the text integrity.

//But this begs the question, why would it be required to match up with such sources? The Masoretic Text is Hebrew. If Christ was speaking in Aramaic, it need not match the Hebrew word-for-word.//

If that is the case then why there is no Aramaic text who support your theory that it is indeed a translation. There are no aramaic sources which match the supposedly “fine”aramaic cited in Matthew. If I included the Markan version this is even more puzzling (see my table above). So much for the “straight” Aramaic expression. Why such an important quotes from such an important event from such an important figure in christendom can not agree with each other.

//He may have been quoting a text, or He may have been employing a translation which existed only orally.//

Employing a no longer extant oral tradition is an interesting proposition. But why such an important quote , the only few evidence of the supposedly aramaic expression of Jesus is not well preserved with speculations of where its original expression . This for me shows how sorry this situation is

//I cannot prove those traditions were known by people observing Christ’s crucifixion, but the existence of such a tradition among Jews does help in showing the plausibility of the connection between that line and Christ’s own suffering being a reference to such.//

I dont see it that way, The psalm opens with a plea from a person in urgent call apparently a serious illness. But the main thrust of the narration is his prayers having been answered, he show obedience to God and preach it to his people. God is praised for his care of all people, and that all people should praise God.

it is hard to believe based from that jewish audience contemporary to Christ will understand that the Messiah was God himself and then He died for their sins

//Have you looked closely at the discussion between God and Iblis, as recounted in surat al-Hijr 15:28-38 and sura Sad 38:71-81, or the discussion between Mary and the angel, as recounted in surat Al `Imran 3:45-49 and sura Maryam 19:17-21?//

These are not different expression. The accounts are complementary. It is also meant pointing up different aspects of an important theme. Also you can not appreciate its literary value if it is not read and recited in original Arabic. If only if we read and memorise the Qur’an in Arabic we will truly appreciate the inter-verses poetic and rhythmic harmony employed by the Qur’an. But this is not the same as the case in allegedly psalm 22 quote in Matthew or Mark as there is no such quote exist anywhere in the canonical hebrew Bible.

//I was not referring to surat an-Nahl (or any other part of the Qur’an), but rather an alternative reading/recitation for the fifth verse of surat al-Qari`a//

I am sorry I misunderstood you. You are talking about the recognised ahruf, yes although there is authentic narration allowing to use the word: صوف in place of عهن . The reason was some arabic dialect in time of the Prophet dont have this term. However if you check all surviving Qu’ranic mushafs around the world, all are uniform using عهن. And neither I have heard this ayat is recited with صوف , this surah is a well known widely memorised surah which I memorised since I was a kid. The fact that the Prophet allowed it means that this is not a textual problem. It is well documented. This is no comparison, you dont have any documented explanation as to why there are different variations in the Psalm quote as found in the greek and syriac testament.

LikeLike

Greetings Eric.

Eric wrote:

{{you are the one who initially brought the “messianic” argument of Psalm 22}}

I noted that there is a Jewish tradition that the relevant Psalm refers to a Messianic figure suffering on behalf of others. That is different from saying such ideas are explicit in the text itself.

***

Eric wrote:

{{does it mention that the messiah will be God incarnate anywhere in chapter 22.}}

I (Denis) responded:

{{No, nor does it claim He will be born of a virgin, but I don’t think there is any requirment for all of the faith to be stated in the 22nd Psalm.}}

Eric replied:

{{Born a virgin is not part of trinitarian formulation the Qur’an condemns.}}

I must confess, I’m at a loss as to the relevance of the Qur’an, here. Is there a rule that Psalm 22 must explicitly affirm those things the Qur’an (allegedly) condemns, but the same Psalm is not required to explicitly affirm things the Qur’an affirms? What would such as rule be based on, and why should a Christian agree to such a rule?

But tacitly, I think your own position grinds close to the point I was attempting to convey: Psalm 22 does not affirm the virgin birth of the Messiah, but it seems to me you would agree that this does not mean that doctrine is therefore false. That leads us to this ruleof thumb: the 22nd Psalm not explicitly affirming a doctrine does not in itself mean we should conclude that doctrine is therefore false.

Eric replied:

{{Even if it is not in the hebrew bible this does not compromise monotheism. The central faith of trinitarianism the Messiah who is also God and then died to atone for people sin.}}

I honestly question the relevance of the Trinity to the question of the Aramaic phrase attributed to Jesus in the Gospels. I am a Trinitarian, but that seems irrelevant to the positions I have taken in this corresponde, because, for example, if I adopted instead a unitarian position (e.g. became a Jeho___’s Witness), my stance on the subject of this thread would remain the same (it would not have an effect on my arguments about Aramaic, translation, statements in variant form, et cetera).

***

Eric wrote:

{{this is still problematic as nowhere then the Matthew expression match with any written evidences of Psalm 22.}}

But this raises a question that I have asked before and ask again now: why would the translation employed by Jesus be required to match another Aramaic translation word for word?

I (Denis) wrote:

{{The statement in Matthew reads as a fine Aramaic translation of the opening of that Psalm}}

Eric replied:

{{I beg to differ, how can anyone can conclusively claim that it is the correct Aramaic expression while none of the supposedly Jesus quoting Psalm expression is exactly the same with each other whether it’s in Masoretic, Aramaic targumim and Syriac NT}}

One quick note: I did not say /the/ correct translation (as if there were only one). Aramaic, like most (if not all?) languages, has words that are synonymous, giving rise to multiple choices when translating certain statements.

As for how anyone can claim that the line in Matthew reads as a fine Aramaic translation of Psalm 22:1, the answer is: via knowledge of Aramaic. A person who is familar with Aramaic can assess whether or not the translation works or not. The line in Matthew is basically the same as the line in Yonatan, save for the fact that the former use l’ma where the latter employs metul ma. But such a difference is merely in precise wording, not meaning, as l’ma and metul ma are basically synonymous, as the former means “why” while the latter means “because of what” (and is used in the sense of why).

As for your appeal to the Masoretic Text, why would an Aramaic translation of a Hebrew text be required to match word for word with that Hebrew text? Translation implies some different words are going to be employed. As for your appeal to other Aramaic translations, do you not acknowledge the possibility of translation employing different words? For example, there are numerous English translations of the Qur’an which might you use different words yet mean the same thing.

Eric wrote:

{{my understanding what those scholars meant by the possible dating is the complete collection of the text itself but their literary origin goes back to Eastern Aramaic Babylonian style which origin undoubtedly pre-dating Christ.}}

Are you saying specifically the scholars you previously mentioned (e.g. Geiger, Rosenthal) took this position? If so, could you share where you feel their writings point in this direction? Secondly, if it is your position that the complete collection of Targum Yonatan was completed after Christ, but portions may predate Him, where does specifically the translation of Psalms fall on that scale?

Eric wrote:

{{but this is not an important point}}

It has some relevance, insofar that if it post-dates Christ, then attacking a translation for not matching a second translation which came /after/ it will seem especially peculiuar, if not unfair.

Eric replied:

{{You still can not deal with the fact that was none of the supposedly Jesus quoting Psalm expression is exactly the same with each other whether it’s in Masoretic, or Aramaic targumim or even Syriac sources.}}

I have addressed this multiple times. The simple response is that different translations are not required to be identical word-for-word, so this is not problematic (and of course a translation is not required to be identical word for word with the text it is translating).

I (Denis) wrote:

{{The Masoretic Text is Hebrew. If Christ was speaking in Aramaic, it need not match the Hebrew word-for-word.}}

Eric replied:

{{If that is the case then why there is no Aramaic text who support your theory that it is indeed a translation.}}

I’m not sure how this addresses the point I was making. I was saying an Aramaic translation of a Hebrew text is not required to match that text word-for-word. You refer to other Aramaic translations, but those translations support this simple point. For example, Targum Yonatan does not match the Masoretic Text word for word.

As for Aramaic texts supporting my claim that the Matthean phrase is a translation of Psalm 22:1, why are other Aramaic texts required to do so? Wouldn’t simple knowledge of Hebrew and Aramaic be sufficient for determining whether one can work as a translation for the other?

Eric wrote:

{{There are no aramaic sources which match the supposedly “fine”aramaic cited in Matthew.}}

But that is irrelevant to assessing the translation itself. Consider an analogy:

(1) Suppose we have the Arabic phrase “bismillahi r-raHmani r-raHeem”.

(2) Suppose someone translates that in English as “in the name of God, the beneficent, the merciful.”

(3) Suppose another person translates it in English as “in the name of Allah, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.”

(4) And then suppose a third person comes along and translates it “in the name of Allah, the merciful, the compassionate.”

We have three different translations. They do not agree word for word. Now, can we judge the third translation based on familiarity with Arabic and English? Or is the only way to measure it is to see if it agrees word for word with either of the other two translations?

Here’s the point of the analogy: you examine a translation based on the languages it is translating from and to. The accuracy of a translation does not rest on whether it matches other translations word for word.

Eric wrote:

{{If I included the Markan version this is even more puzzling. So much for the “straight” Aramaic expression.}}

How does the Markan text undermine the position that the Matthean text works fine as an Aramaic translation of Psalm 22:1? The fact that the Markan text uses a different word does not lead to the conclusion that the Matthean text is therefore problematic as a translation.

Eric wrote:

{{Why such an important quotes from such an important event from such an important figure in christendom can not agree with each other.}}

As I wrote in my very first comment in this thread, apparent repetition of statements in variant form is an interesting question, but I think even you would say such need not be problematic if the meaning remains the same (and there are other approaches as well). This may become more clear as we continue to discuss the Qur’anic texts, below.

***

I (Denis) wrote:

{{the existence of such a tradition among Jews does help in showing the plausibility of the connection between that line and Christ’s own suffering being a reference to such.}}

Eric wrote:

{{I dont see it that way, The psalm opens with a plea from a person in urgent call apparently a serious illness. But the main thrust of the narration is his prayers having been answered, he show obedience to God and preach it to his people. God is praised for his care of all people, and that all people should praise God.}}

First, let’s note that how you intepret the text need not match up with the interpretations put forth in Jewish traditions.

Second, the Psalm does not explicitly refer to the death of the person, but it does not preclude it either. Whether Jewish connects it to the Davidic Messiah or the so-called Josephite/Ephraimite Messiah, other Jewish traditions can have that figure dying as well (even if such is not explicitly stated in Psalm 22 or the traditions which connect Psalm 22 to a suffering Messianic figure).

Eric wrote:

{{it is hard to believe based from that jewish audience contemporary to Christ will understand that the Messiah was God himself and then He died for their sins}}

I didn’t say the relevant Jewish tradition says the relevant Messianic figure is “God Himself”. I was simply noting that there are Jewish traditions which see Psalm 22 as referring to a Messianic figure, as that helps us see the variety of ways Jews have historically seen the text.

***

Turning to the Qur’an…

I (Denis) asked:

{{Have you looked closely at the discussion between God and Iblis, as recounted in surat al-Hijr 15:28-38 and sura Sad 38:71-81, or the discussion between Mary and the angel, as recounted in surat Al `Imran 3:45-49 and sura Maryam 19:17-21?}}

Eric wrote:

{{These are not different expression.}}

The wording is clearly different, so what do you mean? Are they recounting different portions of the same single conversation or are they recounting entirely different conversations? Be clear about how you see those texts. Using those texts, tell me, what precisely did God say to Iblis and what precisely did Iblis say to God? [Feel free to present the statements in Arabic.]

Eric wrote:

{{You are talking about the recognised ahruf, yes although there is authentic narration allowing to use the word: صوف in place of عهن . The reason was some arabic dialect in time of the Prophet dont have this term.}}

So there were versions of surat al-Qari`a that employed Suf rather than `ihn. Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but I suspect your position is that this is fine, because although the different words are employed, they have the same meaning, right?

LikeLike

Hi Denis,

I am sorry in order to avoid repetition, I just comment on only some of your points I deemed relevant to the discussion.

{{-}} Eric bin Kisam

//-// Denis Giron

{{Born a virgin is not part of trinitarian formulation the Qur’an condemns.}}

//I must confess, I’m at a loss as to the relevance of the Qur’an, here. Is there a rule that Psalm 22 must explicitly affirm those things the Qur’an (allegedly) condemns, but the same Psalm is not required to explicitly affirm things the Qur’an affirms? What would such as rule be based on, and why should a Christian agree to such a rule?

But tacitly, I think your own position grinds close to the point I was attempting to convey: Psalm 22 does not affirm the virgin birth of the Messiah, but it seems to me you would agree that this does not mean that doctrine is therefore false. That leads us to this ruleof thumb: the 22nd Psalm not explicitly affirming a doctrine does not in itself mean we should conclude that doctrine is therefore false.//

You are deviating here, you initially brought up ” messianic” and “suffering” and now “the virgin birth” of Psalm 22 argument argument while we are discussing the issue of where Jesus of the gospel got his quote from, I pointed out the Psalm 22 can not be used positively to affirm those doctrines you try to promote during the discussion although we muslims can rely on the Qur’an on the virgin birth.

Now back to the core issue of this post, as christians believe the authority of the hebrew bible and the gospels so this is problematic if Jesus really “quote” the expression from the hebrew bible logically speaking we must expect the exact quotation matches and exists in the divine book of hebrew Bible in original form, word for word not an iota difference nor a translated expression. Unless there there are several forms of this expression exist in the hebrew bible and Jesus use one of the expression. This perhaps should not be an issue.

{{Jesus use expression in Matthew which do not match with any of earlier jewish documents put the claim that he was quoting the opening of the 22nd Psalm into serious doubt.}}

//I would be curious which documents (plural) you have in mind when you refer to those which were “earlier”. Is there any Aramaic version of the Psalms which predates Christ? I do not think there is.

The statement in Matthew reads as a fine Aramaic translation of the opening of that Psalm, and I see no requirement for it match other Aramaic translations, especially if they came later.//

I naturally treat the TaNaKH and its Targumim are all jewish documents supposedly pre-dates Christ, whether or not the final redaction of Tehilim of Targum Yonathan really post-date Christ, I don’t know, but I think, it is not a consensus. What I know from those scholars I cited earlier, they have view that it was written by Babylonian jews so I assume that this assign a dating which goes back to Babylonian Jews had which their traditional interpretation that had been handed down from one generation to another as early as 5th BCE. Moreover you must also know the fact that Targum Jonathan was preliminary oral tradition that reading it from written copy was once prohibited so this makes sense to attribute an pre-christ dating for this Targum back to Babylonian jewry. Even if we must treat this targum as postdating christ, one must remember that the Targum was the authoritative Pharisaic -Rabbinic Aramaic rendering of the hebrew bible, sort of an official aramaic translation. It is interesting to know that Jesus of the gospels do not conform with their rendering.

Again if Jesus indeed intended to the expression from the hebrew bible logically speaking we must expect the he exact quotation matches and exists in original hebrew form, a kind of praying or devotional supplication, (like we muslims do every time with regard to Qur’anic texts) but why he did not do that, did Jesus suppose to know hebrew bible by heart?

//Could you elaborate on which sources you feel endorse a pre-Christian date for Targum Yonatan?//

I can think of Pinkhos Churgin(1894–1957):

This put the Targum Jon starting period as early as the period 2nd century BCE. Later scholars such as Leivy Smolar and Moses Aberbach also support this conclusion.

{{we are seeing a likely scenario that Jesus quote a set of text with different authority no longer intact or that whoever wrote the gospel of Matthew misquote the book of Psalms}}

//He may have been quoting a text, or He may have been employing a translation which existed only orally. Either way, I don’t see how such is problematic in this case. As for the charge of a misquotation, I don’t see how the line in Matthew constitutes a misquote.//

I now understand your position that you believe Jesus used his own expression which is sort of his own everyday translation, (and I still believe this is a mixed expression btw or in diglossic term called a low language), this seems plausible but to me. However it can only mean that Jesus did really mean to invoke Psalmic expression but he was merely praying to his Hashem for help.

//Have you looked closely at the discussion between God and Iblis, as recounted in surat al-Hijr 15:28-38 and sura Sad 38:71-81, or the discussion between Mary and the angel, as recounted in surat Al `Imran 3:45-49 and sura Maryam 19:17-21?//

{{These are not different expression.}}

//The wording is clearly different, so what do you mean? Are they recounting different portions of the same single conversation or are they recounting entirely different conversations? Be clear about how you see those texts. Using those texts, tell me, what precisely did God say to Iblis and what precisely did Iblis say to God? [Feel free to present the statements in Arabic.]//

For God and Iblis story, this is not the actual conversation between God and Iblis and the creation of Adam itself. God retells the conversation to Prophet Muhammad in several way but not be the actual conversation itself (38:71 has a slight additional detail). And for the Angel conversation with Mary those are recounting entirely different conversations with Mary was talking to different parties Angel.

You can not compare this Qur’anic accounts with the supposedly Jesus Psalmic expressions in the Gospels. Christians insist that both Markan Matthean versions are actual quote of T’hillim / Psalm 22:2 make them a “prophecy fulfillment” by Jesus.” If hypothetically there was a scripture by who came later than the Qur’an and claimed a prophecy by quoting Qur’anic passage, then we must expect this prophecy must match the exact expression written in the Arabic Qur’an verbatim not non existent passage.

Whoever tried to make it as if Jesus last words fulfil any prophecy in the TaNaKH They did not do a good job to the text. And I still stick to my understanding that the expression not an actual Hebrew, nor standard Aramaic expression.

{{You are talking about the recognised ahruf, yes although there is authentic narration allowing to use the word: صوف in place of عهن . The reason was some arabic dialect in time of the Prophet dont have this term.}}

//So there were versions of surat al-Qari`a that employed Suf rather than `ihn. Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but I suspect your position is that this is fine, because although the different words are employed, they have the same meaning, right?//

There are no version of the Qur’anic mushaf to my knowledge which use صوف in place of عهن in Suraatul Qaariah but we do know that the Prophet permit it based authentic hadith due to some ancient arabic tribe do not recognize عهن as part of their lexicon.

LikeLike

Greetings Eric

Eric wrote:

{{You are deviating here, you initially brought up ” messianic” and “suffering” and now “the virgin birth” of Psalm 22 argument argument while we are discussing the issue of where Jesus of the gospel got his quote from}}

I would agree that this diverges from the original topic, but recall that such came up in response to you noting that the 22nd Psalm does not say the Messiah is God. My response was simply meant to establish that the Psalm not explicitly affirming some belief need not entail that belief is therefore false.

Eric wrote:

{{Psalm 22 can not be used positively to affirm those doctrines you try to promote during the discussion although we muslims can rely on the Qur’an on the virgin birth.}}

So, again, we get the point I was trying to make: even by your own standards, just because Psalm 22 does not explicitly affirm a belief, that in itself does not mean said belief is therefore false.

But I am happy to get back to the more salient point of the discussion.

Eric wrote:

{{if Jesus really “quote” the expression from the hebrew bible logically speaking we must expect the exact quotation matches and exists in the divine book of hebrew Bible in original form}}

Again, the position I take is that He was putting forth a translation of the text. It should be obvious that a translation of a text does not have to agree word for word with the text being translated. Simply saying translation is not permitted would beg the question of why one should agree with such a rule.

Eric wrote:

{{whether or not the final redaction of Tehilim of Targum Yonathan really post-date Christ, I don’t know}}

But this nonetheless has relevance to your rule that the translation employed by Christ has to mirror the translation employed in Yonatan, word for word. While I see no reason to accept the rule, I would find the rule even more unfair if Yonatan’s translation post-dates Christ.

Now, you appealed to Churgin’s “Targum Jonathan to the Prophets,” but note that the Psalms fall into the Ketubim (i.e. “Hagiographa”). On this subject, note page 20 of that same work refers to “the Targum to Hagiog., which is certainly later than the Targumim to the Pent. and Prophets.” How much later? Well, turn to page 14, note 11, where Churgin interprets [Bavli] Megila 21B as implying that “the Targum to Hag. dates back to the Tanaitic age” [by the way, what exactly Megila says will come up below]. While Churgin strongly rejects the previously discussed position of Geiger which connected Yonatan to Theodotion, this would nonetheless put the translator of the Psalms as potentially a contemporary of Theodotion (depending on where among the age of the Tanaim he falls). Note that Churgin himself sees the Targum to the Prophets as being part of a “long,” “progressive” process, with some portions post-dating the destruction of the Temple (p. 30). If the Targum to the Hagiographa post-dates that corpus, then it seems Churgin’s position does put it after Christ.

Eric wrote:

{{I now understand your position that you believe Jesus used his own expression which is sort of his own everyday translation}}

Not necessarily His own (i.e. not necessarily something He himself made up on which others had previously not heard), but rather I was saying He may have been using a translation that existed orally among the people at that time. Note the Churgin himself states that “[t]he official Targumim are the work of generations. They were formed and reformed through many centuries, gradually, invisibly […and…] are the continuation of the Targumim used in the service.” (pp. 35-36) In other words, it is entirely possible that an extant Targum is a revision of a reading that existed in the past. So, with it being entirely possible that Targum Yonatan to the Psalms post-dates Christ, and with the Targumim at times being revisions of earlier translations, there is nothing implausible about Christ simply employing a translation that existed before the final redaction of Targum Yonatan.

With that in mind, let us turn to Megila 21B. You can see it here (focus on the top six lines):

Click to access hebrewbooks_org_36094_40.pdf

It states that in the period of the Tanaim, there was a rule that, with the Torah, one person recites and one person translates (אהד קורא ואהד מתרגם), while with the Prophets, one person recites and two people can engage in translation (אהד קורא ושנים מתרגמין), while with the Halel (i.e. part of the Psalms) and the Megila, it was permitted to have a situation where ten different men are reciting and ten other men are offering translation (עשרה קורין ועשרה מתרגמין) [Geiger notes that Rashi objects that a Targum to the Ketubim did not exist in the age of the Tanaim]. This, combined with Megila 23b…

Click to access hebrewbooks_org_36094_44.pdf

…having different rules for recitation based on whether a translator (תורגמן) is also present, paints a picture of some men reciting the Hebrew text and other men explaining that text in Aramaic for those who did not understand the Hebrew. Thus we see oral translations existing at that time, which Churgin notes need not reflect extan Targumim. Hence it being entirely plausible that Christ was invoking a translation familiar to some in the audience.

Eric wrote:

{{I still believe this is a mixed expression btw}}

Are you referring to the Matthean reading? If so, on what grounds? Every single word can be found in Jewish Aramaic (in fact, every single word can be found employed in the very Targum you appealed to: that of Yonatan). However, if you mean the Markan reading, I would agree it implies the employment of a Hebrew term for God, but that too was normal practice in Jewish Aramaic. I previously appealed to Onqelos to Genesis 2:22, which employs Elohim:

***

Turning to the Qur’an…

Eric wrote:

{{For God and Iblis story, this is not the actual conversation between God and Iblis and the creation of Adam itself. God retells the conversation to Prophet Muhammad in several way but not be the actual conversation itself}}

See surat al-Hijr 15:32 ans sura Sad 38:75. Each verse seems to be quoting God. Is it your position that even though the Qur’an states that God said such, it need not mean God actually said such? Please elaborate on your position.

Eric wrote:

{{And for the Angel conversation with Mary those are recounting entirely different conversations with Mary was talking to different parties Angel.}}

Compare surat Al `Imran 3:47 (“rabi, ana yakunu li walad(un) walam yasasni bashar(un)”) with sura Maryam 19:20 (“ana yakunu li ghulam(un) walam yamsasni bashar(un)”).

Is it your position that Mary uttered both those statements, at two different times? That she asked essentially the same question after it had already been explained to her a previous time she asked?

And on what grounds do you conclude these are two different events? Being that you hold that God simply recounted His conversation with Iblis in different ways, why couldn’t God likewise recount a single exchange between Mary and an angel in different ways?

Eric wrote:

{{There are no version of the Qur’anic mushaf to my knowledge which use صوف in place of عهن in Suraatul Qaariah but we do know that the Prophet permit it based authentic hadith due to some ancient arabic tribe do not recognize عهن as part of their lexicon.}}

So, again, there were permitted recitations of surat al-Qari`a 101:5 which employed Suf rather than `ihn (and you say this had to do with a difference in dialect). The question I have asked and still would like to ask is this: would it not be your position that the difference is not egregious, being that `ihn and Suf mean the same thing?

LikeLike

With the name of Allah

Hi Denis,

Thanks for your continued interest to this topic. My apology for late reply I was so occupied lately.

{{-}} Eric bin Kisam

//-// Denis Giron

{{if Jesus really “quote” the expression from the hebrew bible logically speaking we must expect the exact quotation matches and exists in the divine book of hebrew Bible in original form}}

//Again, the position I take is that He was putting forth a translation of the text. It should be obvious that a translation of a text does not have to agree word for word with the text being translated. Simply saying translation is not permitted would beg the question of why one should agree with such a rule.//

As I said I see your point but if that is the case then this expression can not truly be said as quoting opening words of canonical Masoretic text of Psalms 22:2.

{{whether or not the final redaction of Tehilim of Targum Yonathan really post-date Christ, I don’t know}}

//But this nonetheless has relevance to your rule that the translation employed by Christ has to mirror the translation employed in Yonatan, word for word. While I see no reason to accept the rule, I would find the rule even more unfair if Yonatan’s translation post-dates Christ.//

It’s a matter of scholarly debate whether or not the final redaction of the Targumim such as the Jonathan post-date Christ however, the targum started as oral tradition. Writing down the targum was prohibited; targumatic writings appeared later and the process span centuries before and after CE (and in case of T Jon it begin with the Babylonian Jews), nevertheless we should expect that the oral and the written targums were the same otherwise we can dismiss the written Targums as bogus and un-authoritative as they were not carefully preserved.

//Now, you appealed to Churgin’s “Targum Jonathan to the Prophets,” but note that the Psalms fall into the Ketubim (i.e. “Hagiographa”). On this subject, note page 20 of that same work refers to “the Targum to Hagiog., which is certainly later than the Targumim to the Pent. and Prophets.”//

Targum Hagiog is later relative to Targum to Prophets, yes, but nowehere it says it predates Christ.

//How much later? Well, turn to page 14, note 11, where Churgin interprets [Bavli] Megila 21B as implying that “the Targum to Hag. dates back to the Tanaitic age”.//

I do not see that Churgin interpret Babli Megillah as implying its date from Tanaitic era he was discussing the opinion among targum scholars who suggest Rab Joseph as the real author of Targum Jon while in fact Rab Joseph cites Targum Jon with introductory phrase אלמל תרגומא דהאי קרא which clearly signifies that he had the Targum before him. If for argument sake we accept that Targum Jon final redaction dates back to Tanaitic era (10 C.E onward) do not necessarily mean post-dating Christ supposedly Crucifixion which was thought about 30-40 C.E. Also bear in mind that even that this written version are based on much older oral tradition that the era of crucifixion.

{{I now understand your position that you believe Jesus used his own expression which is sort of his own everyday translation}}

//Not necessarily His own (i.e. not necessarily something He himself made up on which others had previously not heard), but rather I was saying He may have been using a translation that existed orally among the people at that time.

With that in mind, let us turn to Megila 21B. You can see it here (focus on the top six lines):

http://hebrewbooks.org/pagefeed/hebrewbooks_org_36094_40.pdf

This, combined with Megila 23b…

http://hebrewbooks.org/pagefeed/hebrewbooks_org_36094_44.pdf

Thus we see oral translations existing at that time, which Churgin notes need not reflect extan Targumim. Hence it being entirely plausible that Christ was invoking a translation familiar to some in the audience.//

Thanks for the Hebrew talmudic references , from what my understanding, the sage basically were saying with all this rules of reasding the TaNaKh is that one not only hear the reading, but also understand it. Nowhere it indicates that מתרגמין actually means different translation other than the one who read the translation. Rashi wrote in his comentary on Megillah 21b6 ועשרה מתרגמין – לא גרסינן שאין תרגום בכתובים which he seems to suggest that there was no text with Ketubim translation lo garsinan sheyin targum b’ketubim , so the translation here means the formal Aramaic extant recitation which was based on the oral recitation not the loose translation.

{{I still believe this is a mixed expression btw}}

//Are you referring to the Matthean reading? If so, on what grounds? Every single word can be found in Jewish Aramaic (in fact, every single word can be found employed in the very Targum you appealed to: that of Yonatan). However, if you mean the Markan reading, I would agree it implies the employment of a Hebrew term for God, but that too was normal practice in Jewish Aramaic. I previously appealed to Onqelos to Genesis 2:22, which employs Elohim://

Yes, Im referring to Matthew rendering. The problem with this Aramaic expression it contains לָמָה lamah or לָמָּה lammah. Those are Hebrew for the interrogative particle “why?” and is not normally used in Aramaic – the Aramaic equivalent is אַמַּי or אַמַּאי ammai or, in literary Aramaic such as that used by Targum Jon, מְטוּל מַה methul mah (although Ezra does use the hybrid לְמָה lemah “for what?” twice in his Aramaic passages – in 4:22 and 7:23, but this too a hybrid Hebrew and Aramaic expression). Also the word El אלִ֣ too is not a correct form for God in Aramaic, which should be Elah אלה.

{And for the Angel conversation with Mary those are recounting entirely different conversations with Mary was talking to different parties Angel.}}

//Compare surat Al `Imran 3:47 with sura Maryam 19:20

Is it your position that Mary uttered both those statements, at two different times?

And on what grounds do you conclude these are two different events? Being that you hold that God simply recounted His conversation with Iblis in different ways, why couldn’t God likewise recount a single exchange between Mary and an angel in different ways?//

Yes, it was different times, the 19:17 we read فَأَرْسَلْنَا إِلَيْهَا رُوحَنَا, the word here is singular رُوحَ ie. Spirit not أَرْوَاح Spirits, so there is one Angel which was in conversation with Mary, while in 3:44 it speaks إِذْ قَالَتِ الْمَلَائِكَةُ, so there it is مَلَائِكة Angels , more than two angels had conversation with Mary (peace be upon her).

{{There are no version of the Qur’anic mushaf to my knowledge which use صوف in place of عهن in Suraatul Qaariah but we do know that the Prophet permit it based authentic hadith due to some ancient arabic tribe do not recognize عهن as part of their lexicon.}}

//So, again, there were permitted recitations of surat al-Qari`a 101:5 which employed Suf rather than `ihn (and you say this had to do with a difference in dialect). The question I have asked and still would like to ask is this: would it not be your position that the difference is not egregious, being that `ihn and Suf mean the same thing?//

These are accepted and recognized way of reciting it, but the original recitation itself is always “وَتَكُونُ الْجِبَالُ كَالْعِهْنِ الْمَنفُوشِ” not “وَتَكُونُ الْجِبَالُ كَالْصوف الْمَنفُوشِ” as I said this surah is one of short surah almost all muslim kids must memorize as part of their Islamic education. While in case of Matthew supposedly Psalmic expression, you dont have any basis whatsoever other than postulating Jesus (peace be upon him) was quoting a non-extant text of Targumim.

LikeLike

Quick note: I’m writing these posts very quickly, and thus a lot of typos are coming out. Particularly egregious is the repeated rendering of eHad (אחד) as ehad with a heh rather than Het (אהד). That was because I was coping and pasting from the readable PDF I linked to, without checking closely how the pasting was coming out.

LikeLike

This is very interesting.

So do you think this could be an indication of the person on the cross who uttered those words was NOT quoting from the Psalms but was actually speaking an everyday dialect and genuinely was expressing regret that God had abandoned him?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, the fact is the expression appear to be a mixed Aramaic and hebrew rather than commonly understood as Aramaic is a solid evidence that Jesus definitely did not mean to quote Psalms rather Jesus really have thought himself as being abandoned from God, and asked for his help. We know from the Qur’an that he was indeed saved by God.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings Eric

When you refer to the text as a mix of Aramaic and Hebrew, how does such apply to the Matthean text? The entire phrase works perfectly as Aramaic (i.e. every word employed therein can be found in Aramaic — in fact every word therein can be found even in Targum Yonatan).

If one wishes to point to a mix of Hebrew and Aramaic, the Markan text might be the better candidate (as the employment of the Greek omega in the transliteration seems to clearly imply a distinctly Hebrew word for God). But even there, that sort of trend is fairly common in Jewish Aramaic. For example, see Genesis 2:22 in Targum Onqelos or Yerushalmi (PseudoYonatan), as Elohim is employed (so too, if memory serves correct, Elohai appears in Yerushalmi/PseudoYonatan to Numbers 22:18, but I need to check my edition when I get home, as I’m at the office now). Rabbinic literature is littered with examples of Aramaic texts employing Elohim, Elohai, Eloheyka, et cetera.

And this sort of phenomenon should not be surprising in environments where both Aramaic and Hebrew are employed. For an analogy, have you ever looked into the Raqush inscription? It was produced in an environment where Aramaic and Arabic were employed, and it produces a seamless mix of the two such that scholars disagree as to whether its an Aramaic text employing Arabisms or an Arabic text employing Aramaisms.

LikeLike

With the Name of Allah

Hi Denis,

//When you refer to the text as a mix of Aramaic and Hebrew, how does such apply to the Matthean text? The entire phrase works perfectly as Aramaic (i.e. every word employed therein can be found in Aramaic — in fact every word therein can be found even in Targum Yonatan).//

The expression is a mixed bag on two grounds first I tend to think that the word “Eli” אלי is Hebrew (the more correct format for God, I think, is Elah אלה, the evidence in Mark that it use eloi, is which is most likely due to mis-transliteration of Aramaic Elah). Second the word “methul” מטול in Targum translation (which is dropped in Matthew ) is Aramaic. This usage is not found in anywhere Masoretic text).

But again this is beside the point, the fact is the wording of this expression differ from any known expression of the canonical book of Psalms and its translation. I dont find it satisfactory to try to explain the relationship between the Matthew quote Psalm 22 saying that it was normal practise of speech switch between Hebrew and Aramaic. We are supposedly talking about the unchanging word of God here, if Jesus meant to quote Psalm then the expression must be the original psalmic quote otherwise I see it as an evidence of textual corruption or just an attempt for those who want the verse to appear that Jesus “accomplished” God’s plan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greetings Eric

Eric wrote:

{{I tend to think that the word “Eli” אלי is Hebrew}}

But is not the very Targum you appealed to (that of Yonatan) evidence that such is also employed in Jewish Aramaic? See the underlined text in the second of the two images you employed in your own article.

Eric wrote:

{{Second the word “methul” מטול in Targum translation (which is dropped in Matthew ) is Aramaic. This usage is not found in anywhere Masoretic text).}}

Yes, metul ma (“because of what,” “for what reason,” i.e. “why”) is not found in the Masoretic Text. It’s an Aramaic construction, so we should not be surprised if it does not appear in a Hebrew text. But I don’t see how that means the phrase in Matthew is therefore not Aramaic. Perhaps you meant to argue that the Matthean phrase *should have* employed metul ma? If so, note that lama is also part of Aramaic (Yonatan uses it several times).

Eric wrote:

{{the wording of this expression differ from any known expression of the canonical book of Psalms and its translation.}}

An Aramaic translation of a Hebrew phrase differing from that phrase should not surprise us. As for it differing from other translations, this begs the question: why should the translation be required to match other translations (especially if those other translations came later)?

Eric wrote:

{{I dont find it satisfactory to try to explain the relationship between the Matthew quote Psalm 22 saying that it was normal practise of speech switch between Hebrew and Aramaic.}}

That would apply more to the Markan text (as the omega in the Greek transliteration seems to imply a distinctly Hebrew word). But that does occur in Jewish Aramaic, too.

Eric wrote:

{{We are supposedly talking about the unchanging word of God here, if Jesus meant to quote Psalm then the expression must be the original psalmic quote}}

I disagree. For example, if I quote the Qur’an to English speakers, or Spanish speakers, I do not think I am forbidden from putting forth a translation in their language. And, with the Markan reading in mind, if I am permitted to employ translation, I do not believe I would be forced to only use one word in reference for the Creator; rather I believe I would have multiple options from different languages (e.g. God, Dios, Allah).

Eric wrote:

{{I see it as an evidence of textual corruption}}

I honestly do not think mere translation constitutes textual corruption.

LikeLike

Eric wrote:

<>

This of course begs the question, did He in fact think He was being abandoned by God? Your own article acknowledges that others believe He was quoting (or paraphrasing) the opening of the 22nd Psalm, a text, interestingly enough, which some Jewish sources (e.g. Pesīqtā Rabatī) saw as referring to a Messianic figure suffering on behalf of others. Just as if I paraphrase/quote the opening of that Psalm in English, it need not entail I believe God has abandoned me, so too with Christ. In light of the relevant Jewish tradition, it is at least possible He was subtly drawing those familiar with the Psalm towards the conclusion that while it might look like the end, there was still “more to come”.

Eric wrote:

<>

It is certainly an interesting subject (by the way, it is interesting to note that the Psalm itself, at least in its Masoretic version, transitions from Elī in the opening to Elohai in the text which immediately follows, and the Peshīttā to the Psalm employs Alahī). Whatever the case, apparent quotations in variant form is an interesting subject, and one which appears in the Qur’ān as well (e.g. compare the accounts of God and Iblīs or Mary and the angel). Some might argue that variant quotations are permissible if the meaning remains the same (perhaps analogous is sūrat al-Qāri`a(t) 101:5 having `ihn in some readings and sūf in others, both meaning wool). But I have encountered others who have posited that some seemingly repetitious Qur’ānic texts are actually giving fragments of discussions which actually employed repetition (e.g. perhaps God asked Iblīs the same question in two different ways). If that sort of phenomenon is possible, while I would be reluctant to propose it for the cry on the Cross, it at least might explain why some wrongly thought He was invoking Eliyah.

Eric asked:

<>

The employment of the verb lishboq generally makes one lean towards Aramaic, but in the roughly contemporary Talmūd we can see almost effortless switchess between Hebrew and Aramaic (sometimes in the same single sentence), so He may have been quoting it in a form of Aramaic which was very close to Hebrew.

Eric wrote:

<>

Or He simply quoted/paraphrased it in a way which was popular among people in the audience. In that time, it may very well been the case that literate persons would quote the Scriptures in Hebrew and explain them in Aramaic, therefore an oral form popular among certain people could have easily reflected that.

I would not a similar phenomenon exists among Jews, today, where popular oral translations don’t reflect extant text translations. For example, among some Hasidic Jews (especially Lubavitchers), in recent years it has become popular to render she’ol as “purgatory”. I have even seen this when a rabbi is paraphrasing Rabbinic texts (e.g. a Talmūdic passage) yet the popular oral translation is not reflected in extant official print translations.

Eric wrote:

<>

I think it is clear He was not simply quoting what would become the Masoretic Text (by virtue of His using lishboq rather than la`azob).

Eric wrote:

<>

Of course not, as Onqelos did not translate Psalms.

Eric wrote:

<>

Clearly no (I think, with the exception of orthodox Jews who insist the historical Yonatan really is the sole translator, most would treat Targūm Yonatan as post-dating Christ).

Eric wrote:

<>

Indeed, extant Jewish Targūmīm do not do so. But there is nothing implausible about alternatively employing lama (which, though not appearing in this verse, nonetheless is employed elsewhere in Targūm Yonatan), and surely Christ would not be limited to texts extant in our time (as was alluded to above, He need not be limited to texts period).

LikeLike

YIKES! It looks like my use of angle brackets backfired on me, with all the quoted text disappearing. So permit me to repost with a different style of quoting (i.e. please forgive this repetition).

Eric wrote:

“Why should Jesus have thought himself as being abandoned from God”

This of course begs the question, did He in fact think He was being abandoned by God? Your own article acknowledges that others believe He was quoting (or paraphrasing) the opening of the 22nd Psalm, a text, interestingly enough, which some Jewish sources (e.g. Pesīqtā Rabatī) saw as referring to a Messianic figure suffering on behalf of others. Just as if I paraphrase/quote the opening of that Psalm in English, it need not entail I believe God has abandoned me, so too with Christ. In light of the relevant Jewish tradition, it is at least possible He was subtly drawing those familiar with the Psalm towards the conclusion that while it might look like the end, there was still “more to come”.

Eric wrote:

“Mark 15:34 uses eloi instead of eli and this surely is an interesting discrepancy”

It is certainly an interesting subject (by the way, it is interesting to note that the Psalm itself, at least in its Masoretic version, transitions from Elī in the opening to Elohai in the text which immediately follows, and the Peshīttā to the Psalm employs Alahī). Whatever the case, apparent quotations in variant form is an interesting subject, and one which appears in the Qur’ān as well (e.g. compare the accounts of God and Iblīs or Mary and the angel). Some might argue that variant quotations are permissible if the meaning remains the same (perhaps analogous is sūrat al-Qāri`a(t) 101:5 having `ihn in some readings and sūf in others, both meaning wool). But I have encountered others who have posited that some seemingly repetitious Qur’ānic texts are actually giving fragments of discussions which actually employed repetition (e.g. perhaps God asked Iblīs the same question in two different ways). If that sort of phenomenon is possible, while I would be reluctant to propose it for the cry on the Cross, it at least might explain why some wrongly thought He was invoking Eliyah.

Eric asked:

“Fine, now wait a minute, that “Eli Eli lama sabachthani ” is it an Aramaic or Hebrew expression?”

The employment of the verb lishboq generally makes one lean towards Aramaic, but in the roughly contemporary Talmūd we can see almost effortless switchess between Hebrew and Aramaic (sometimes in the same single sentence), so He may have been quoting it in a form of Aramaic which was very close to Hebrew.

Eric wrote:

“We are left for just two options for the origin of this expression: whether (1) Jesus quoted Masoretic Hebrew text or (2) the Aramaic Targums.”

Or He simply quoted/paraphrased it in a way which was popular among people in the audience. In that time, it may very well been the case that literate persons would quote the Scriptures in Hebrew and explain them in Aramaic, therefore an oral form popular among certain people could have easily reflected that.

I would not a similar phenomenon exists among Jews, today, where popular oral translations don’t reflect extant text translations. For example, among some Hasidic Jews (especially Lubavitchers), in recent years it has become popular to render she’ol as “purgatory”. I have even seen this when a rabbi is paraphrasing Rabbinic texts (e.g. a Talmūdic passage) yet the popular oral translation is not reflected in extant official print translations.

Eric wrote:

“If Jesus did quote this expression from Masoretic Hebrew text…”

I think it is clear He was not simply quoting what would become the Masoretic Text (by virtue of His using lishboq rather than la`azob).

Eric wrote:

“If Jesus meant to quote Aramaic Targums. is it Targum Onqelos”

Of course not, as Onqelos did not translate Psalms.

Eric wrote:

“or Targum Yonathan”

Clearly no (I think, with the exception of orthodox Jews who insist the historical Yonatan really is the sole translator, most would treat Targūm Yonatan as post-dating Christ).

Eric wrote:

“I doubt that there is such expression because Aramaic Targums do not say “Lema […] but instead […] Methul ma”

Indeed, extant Jewish Targūmīm do not do so. But there is nothing implausible about alternatively employing lama (which, though not appearing in this verse, nonetheless is employed elsewhere in Targūm Yonatan), and surely Christ would not be limited to texts extant in our time (as was alluded to above, He need not be limited to texts period).

LikeLiked by 1 person

With the Name of Allah

Hi Denis,

Thanks for your comment,

//He was quoting (or paraphrasing) the opening of the 22nd Psalm, a text, interestingly enough, which some Jewish sources (e.g. Pesīqtā Rabatī) saw as referring to a Messianic figure suffering on behalf of others//

Even if it is accurate I have no problem accepting messianic nature of this chapter, Muslims believe Jesus is the messiah for the Jews, but the problem is did the messiah die?, does it mention that the messiah will be God incarnate anywhere in chapter 22. That is the real question you should ponder, but that’s a discussion for another topic. The fact that Jesus use expression in Matthew which do not match with any of earlier jewish documents put the claim that he was quoting the opening of the 22nd Psalm into serious doubt.

//Whatever the case, apparent quotations in variant form is an interesting subject, and one which appears in the Qur’ān as well (e.g. compare the accounts of God and Iblīs or Mary and the angel). Some might argue that variant quotations are permissible if the meaning remains the same (perhaps analogous is sūrat al-Qāri`a(t) 101:5 having `ihn in some readings and sūf in others, both meaning wool).//

The Qur’an don’t have variant forms expression for one particular event. The term عِهْن in وَتَكُونُ الْجِبَالُ كَالْعِهْنِ in Suratul Qari’ah is unrelated to أَصْوَافِ in Suratun Nahl. These two describe separate event.

// in the roughly contemporary Talmūd we can see almost effortless switchess between Hebrew and Aramaic (sometimes in the same single sentence), so He may have been quoting it in a form of Aramaic which was very close to Hebrew.//

Maybe, but even if we are to accept this hybrid expression theory the problem is none of the aforementioned expression in Matthew can be found in any canonical masoretic text nor in its Aramaic translation.

//He simply quoted/paraphrased it in a way which was popular among people in the audience. In that time, it may very well been the case that literate persons would quote the Scriptures in Hebrew and explain them in Aramaic//

Jesus cried out in agony while uttering this expression on the cross, he did not deliver a sermon and nor preaching

//Clearly no (I think, with the exception of orthodox Jews who insist the historical Yonatan really is the sole translator, most would treat Targūm Yonatan as post-dating Christ).//

This is far from being a scholarly consensus, Onqelos and Yonatan, some scholars like A. Geiger, Franz Rosenthal, H.L. Ginsberg etc. , argue that they were written by Babylonian jews hardly unlikely that it is post-dating christ.

//and surely Christ would not be limited to texts extant in our time (as was alluded to above, He need not be limited to texts period).//

But you miss the point here, the fact that no expression in Matthew can be found in any canonical masoretic text nor in its Aramaic translation imply a good evidence where the text of the old testament bible canon were fluid and we are seeing a likely scenario that Jesus quote a set of text with different authority no longer intact or that whoever wrote the gospel of Matthew misquote the book of Psalms due to their infallibility or Id say un-familiarity with Jewish texts. Or other possibility is plausible of course that Jesus did not mean to quote Psalms at all and he used colloquial expression, asking God for help during his terrible ordeal at the cross.

LikeLike

Greetings Eric

[Quick note: the order in which I respond to your comments differs slightly from the order in which they appeared in your post, as I am attempting to group some common themses together.]

Eric wrote:

{{the problem is did the messiah die?}}

As you mentioned, this is a discussion for another topic, but I would at least note that the two sources which attribute the relevant statement to Christ both seem to be pretty clear in stating that He died. However, if you’re asking if Psalm 22 refers to the death of the Messiah, I would say no (at least not in any explicit or obvious way).

Eric wrote:

{{does it mention that the messiah will be God incarnate anywhere in chapter 22.}}

No, nor does it claim He will be born of a virgin, but I don’t think there is any requirment for all of the faith to be stated in the 22nd Psalm.

Eric wrote:

{{Jesus use expression in Matthew which do not match with any of earlier jewish documents put the claim that he was quoting the opening of the 22nd Psalm into serious doubt.}}

I would be curious which documents (plural) you have in mind when you refer to those which were “earlier”. Is there any Aramaic version of the Psalms which predates Christ? I do not think there is.

The statement in Matthew reads as a fine Aramaic translation of the opening of that Psalm, and I see no requirement for it match other Aramaic translations, especially if they came later. Which brings us to your statement about the dating of Yonatan:

Eric wrote:

{{some scholars like A. Geiger, Franz Rosenthal, H.L. Ginsberg etc. , argue that they were written by Babylonian jews hardly unlikely that it is post-dating christ.}}

Geiger’s “Urschrift und Übersetzungen der Bibel” is available online…

Click to access urschriftundb00geiguoft.pdf

…and on pages 163-164 he discusses Yonatan in general, pushing the (admittedly now widely rejected) theory that Yonatan was actually connected to Theodotion (that would put the translations attributed to him as much as a century after Christ). He does treat the Targum as receiving its redaction in Babylonian circles, but connects it to the rough time of the Gemara (which, again, would put it well after Christ). I’m not claiming Geiger’s views must be accepted, but, since you cited him, I wanted to note that I see no evidence that he considered Targum Yonatan to predate Jesus.

While I don’t have an online version, I would note that pages 130-131 of Rosenthal’s “Die Aramaistische Forschung” treat the language of Yonatan as Babylonian, but dates it to within the first four centuries of the Christian era.

Could you elaborate on which sources you feel endorse a pre-Christian date for Targum Yonatan?

Eric wrote:

{{even if we are to accept this hybrid expression theory the problem is none of the aforementioned expression in Matthew can be found in any canonical masoretic text nor in its Aramaic translation.}}

But this begs the question, why would it be required to match up with such sources? The Masoretic Text is Hebrew. If Christ was speaking in Aramaic, it need not match the Hebrew word-for-word. Nor is there any requirment for His Aramaic translation to match that of someone else, as discussed above.

Eric wrote:

{{the fact that no expression in Matthew can be found in any canonical masoretic text nor in its Aramaic translation imply a good evidence where the text of the old testament bible canon were fluid}}

As I wrote above, the line in Matthew reads as a straight Aramaic translation of the opening Psalm 22. There is nothing in that translation which entails a variant reading [in other words, while some NT texts employs translations which clearly diverge from the Masoretic Text, this is not a case of such].

Eric wrote:

{{we are seeing a likely scenario that Jesus quote a set of text with different authority no longer intact or that whoever wrote the gospel of Matthew misquote the book of Psalms}}

He may have been quoting a text, or He may have been employing a translation which existed only orally. Either way, I don’t see how such is problematic in this case. As for the charge of a misquotation, I don’t see how the line in Matthew constitutes a misquote.

Eric wrote:

{{Jesus cried out in agony while uttering this expression on the cross}}

He made the statement on the cross, and the statement just happens to read as a straightforward Aramaic translation of the opening of the 22nd Psalm. As was previously noted, this is a Psalm which, interestingly enough, is treated by traditions recorded in later Rabbinic texts as referring to a Messianic figure who would suffer on behalf of others. I cannot prove those traditions were known by people observing Christ’s crucifixion, but the existence of such a tradition among Jews does help in showing the plausibility of the connection between that line and Christ’s own suffering being a reference to such.

On the subject of the Qur’an (with relevance to questions of how we address differences in wording that do not constitute differences in meaning)…

Eric wrote:

{{The Qur’an don’t have variant forms expression for one particular event.}}

Have you looked closely at the discussion between God and Iblis, as recounted in surat al-Hijr 15:28-38 and sura Sad 38:71-81, or the discussion between Mary and the angel, as recounted in surat Al `Imran 3:45-49 and sura Maryam 19:17-21?

Eric wrote:

{{The term عِهْن in وَتَكُونُ الْجِبَالُ كَالْعِهْنِ in Suratul Qari’ah is unrelated to أَصْوَافِ in Suratun Nahl.}}

I was not referring to surat an-Nahl (or any other part of the Qur’an), but rather an alternative reading/recitation for the fifth verse of surat al-Qari`a (though not one that changes the meaning of the verse). I’m running out of time, here, so permit me to at least point out that quick Google search will reveal lots of sites discussing the subject:

https://www.google.com/search?q=%22%D9%88%D8%AA%D9%83%D9%88%D9%86+%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84+%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D9%88%D9%81+%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%86%D9%81%D9%88%D8%B4%22&oq=%22%D9%88%D8%AA%D9%83%D9%88%D9%86+%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84+%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D9%88%D9%81+%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%86%D9%81%D9%88%D8%B4%22

LikeLike

Jesus didn’t quote anything of course, He merely said it on the moment, fulfilling yet more Biblical prophecy and thus establishing Himself as the prophesied Messiah of God of the Old Testament.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Which biblical prophecy he was supposed to fulfill if he didn’t quote the hebrew bible?

He simply cried to his God to save him.

LikeLike

The prophesy was not to quote the Old Testament, otherwise it’s not a prophecy. The Old Testament merely prophesied of Jesus words on the cross, and it was correct. Do you follow this logic?

LikeLike