For western rite Roman Catholics and some Protestants (e.g. many Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Presbyterians), today is Ash Wednesday, a day on which they recommit themselves to their faith, while looking forward to Easter (Pascha). The most recognizable aspect of the day is the ash crosses which the faithful receive upon their foreheads.

Every year, around this time, there are voices which wonder aloud (some sincerely, others polemically), where is Ash Wednesday in the Bible? The simple answer is that it has no explicit mention in Scripture.[1] However, this article will briefly look at some interesting parallels which arise when the day is considered against the backdrop of the Bible and Jewish tradition. While many who discuss this subject will invoke Jesus fasting for forty days as the inspiration (as the period between Ash Wednesday and Easter is forty days if the Sundays within that span are excluded from the count), there is more that can be brought up.

Reaffirmation A Month Before Passover

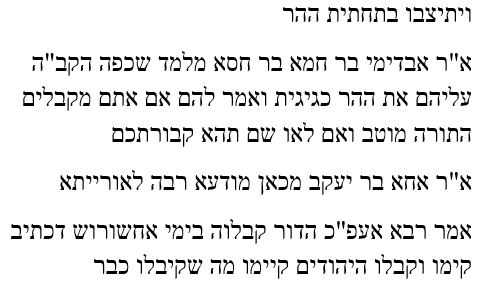

One interesting place to begin such an exploration is Talmūd Bavlī, tractate Shabat 88A, which reads as follows:

“And they stationed themselves at the bottom of the mountain” [Exodus 19:17]

Rabbi Ābdīmī bar Hamā bar Hasā said: it is taught that the Holy One, blessed be He, upturned the mountain over them,[2] like a tub, and He said to them, “if you receive the Torah, good, but if not, then this here will be your burial.”

Rabbi ĀHā bar Ya`qob said [in reply]: from this there is a great objection to the Torah!

Rabā said [in reply]: even so, the generation in the days of ĀHashweros received it, as it is written [in Esther 9:27]: “the Jews confirmed[3] and received” — they confirmed what they received.

What’s significant about that passage is that it invokes a verse from Esther which is actually discussing the establishment of Pūrīm. Th passage records an ancient Jewish tradition which held that the believers essentially recommitted themselves to their faith around the time of Pūrīm, which just so happens to fall a lunar month before Passover.

Marking Foreheads A Month+ Before Yom Kīpūr

Keeping the above in mind, but switching gears, another text worth considering is the Biblical verse at Ezekiel 8:1. That verse provides the date for a vision which would encompass events described in the rest of the chapter and the chapter which follows (which is to say, chapter 9). The date is the fifth day of the sixth month, which is slightly over a month before Yom Kīpūr (the day of atonement).

Also significant is Ezekiel 9:4-6, where an order is given to place a mark on the heads of certain people. Those who lack the mark will be executed, while those who have the relevant mark on their forehead will be spared. A fun question to ask at this point is, what would the proposed mark look like?

Interestingly, the Hebrew text refers to it as a taw (תו), which is the name of the last letter of the Hebrew Bible, which just so happened to be a cruciform (either x or +) in the older, Phoenician script which Hebrew was once written in.[4] The entry for taw in Gesenius’ Lexicon[5] notes this:

The Messiah’s Feast

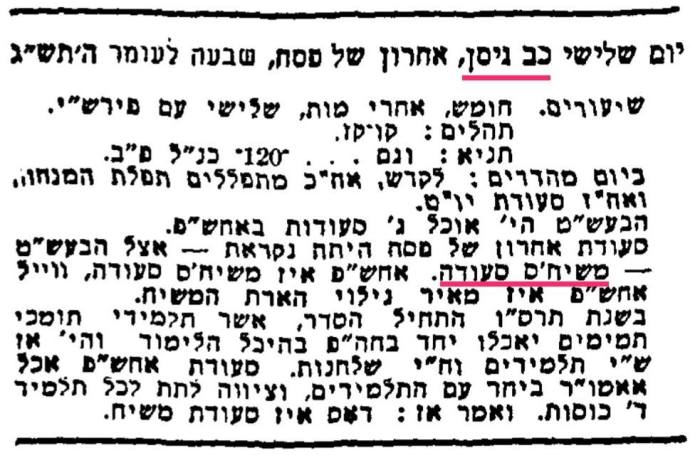

Before tying these various, disparate threads together, one more (perhaps lighthearted) example may be worth considering, that being the entry for the 22nd of Nīsan (i.e. the date one week after the start of Passover), on page 47 of the Orthodox Jewish work, Ha-Yom Yom[6]:

In this work, it is noted that the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Hasidic movement within Orthodox Judaism, established 22 Nīsan as “the Messiah’s feast”. Note that 22 Nīsan is almost forty days after Pūrīm, the date in which ancient Jewish tradition holds believers recommitted themselves to the word of God.

Tying It All Together

At this point, the text above might strike a reader as little more than a collection of seemingly interesting yet nonetheless unrelated trivia. However, it is now that one can begin to paint an intriguing picture. Note the following:

- The New Testament treats the Old Testament feasts as foreshadowings of Christ (cf. Colossians 2:16-17).

- The New Testament reinterprets the Passover in light of Christ (cf. 1 Corinthians 5:7).[7]

- Ancient Jewish tradition records a religious day established by believers, and falling a month before Passover, as also being a day on which believers reconfirmed their faith.

- Ancient Christian tradition treated Yom Kīpūr as foreshadowing the sacrifice of Christ.[8]

- An Old Testament text can be understood as having cruciforms placed on the foreheads of faithful believers a little over a month before Yom Kīpūr.

- Later Jewish mystics, in their contemplation of their own traditions, established a feast dedicated to the Messiah, which falls slightly after the start of Passover, and falls nearly forty days after the above-mentioned day on which the believers recommitted themselves to the faith.

With all that laid out, note that Ash Wednesday is a time when believers have a cruciform marked on their forehead, and recommit themselves to the faith. It falls slightly over forty days before Good Friday (which one scholar referred to as “the great eschatological Day of Atonement”[9]) and slightly over forty days before the veritable Messiah’s feast (Pascha/Easter) which falls slightly after the start of the old, traditional Passover. While the concepts are not identical, Ash Wednesday, when understood in such a way, seems to fit rather comfortably among the Biblical texts and Jewish traditions discussed above.

________

NOTES:

(1) As has come up in previous blog entries (e.g. the entry on Halloween), the Bible and Jewish literature take it for granted that the believers can establish new feasts and other sorts of religious days, with Pūrīm (in the book of Esther) and Hanūkkah (in the books of Maccabees and Rabbinic tradition) being easy examples of such. Moreover, the New Testament states that Christ bestowed upon the Episcopacy the authority to ‘bind and loose’ (cf. Matthew 16:19, Matthew 18:18), which parallels a similar authority found in Isaiah 22:20-22. In light of the already existing Old Testament precedent of believers establishing new feasts, this authority to ‘bind and loose’ plausibly includes the the continued ability to establish new religious days. Therefore, Ash Wednesday not being found in the Bible can nonetheless be explained in that light, but this entry seeks to go deeper, still.

(2) It may be worth noting that this seems to be describing the same event which is referred to in the Qur’ān, in sūrat al-Baqarah 2:63, sūrat al-Baqarah 2:93, and sūrat an-Nisā’ 4:154 (though the accounts are not identical). [Disclaimer for more polemically minded readers: mentioning that a story is recounted in both the Talmūd and the Qur’ān is not intended here as a charge of “borrowing,” nor is such intended to cast aspersions on the historicity of either version of the story.]

(3) The verb qīmū generally means they raised or established, but the translation chosen here is meant to reflect the interpretation of the relevant Talmūdic sage.

(4) While there are many resources on the subject of the Hebrew script, one easily accessible source, available in a great many libraries and book stores, is the chart in Ben Yehuda’s Pocket Hebrew-English Dictionary, which puts the ancient Phoenician (or “Paleo-Hebrew”) script side-by-side the currently used Āshūrī (or standard Hebrew) script, as well as its later developed cursive form.

(5) William Gesenius, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Boston, MA: Crocker and Brewster, 1850), p. 1097.

(6) The book is attributed to the sixth and seventh Lubavitcher Rebbes (i.e. rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn and rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, respectively), and can be read online, here: http://beta.hebrewbooks.org/43302

(7) A straight reading of the Synoptic Gospels gives the strong impression that the Last Supper was a Passover seder (one can get a different impression from John, which is an interesting subject unto itself). If the Last Supper was a Passover seder, that would imply Passover had already started before the Crucifixion, which would mean Christ (regognized by Christians as their Passover lamb) was sacrificed after the start of the old, traditional, quartodeciman Passover. This in itself would provide Biblical support for holding the Christian Pascha (the Passover reinterpreted in light of Christ, called “Easter” in Teutonic languages) on a date slightly after the start of the quartodeciman date.

(8) This comes up, among other places, in the fortieth chapter of Justin Martyr’a Dialogue With Trypho, as well as in the seventh chapter of the Epistle of Barnabas.

(9) Jürgen Roloff, “ιλασμος,” in Horst Balz & Gerhard Schneider (eds.), Exegetical Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1991), vol. 2, p. 186.

Categories: Catholicism, Christianity, Judaism

التواء Attwa’ is still used among Arabs ( marks on their camels). After Islam, the prophet pbuh forbade doing that on the animals’ faces.

Jabir reported that Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) forbade (the animals to be beaten) on the face or branding on the face.” Sahih Muslim

LikeLike

Indiana Giron and the quest for the holy ashtag

LikeLike

Salaam,

It seems that Dennis often attempts to pull various unrelated threads together in order to stretch interpretations and make loose and often times weak connections in order to justify unjustifiable practices and traditions that are not supported by his very own Bible itself. The very fact that is obligated to do such illustrates a great weakness in the Christian religion, its traditions and practices.

As he already pointed out there is no explicit mention of Ash Wednesday in Biblical Scripture (One would think the conversation would end there). As we have seen on this blog and in other scholarly publications, NT reinterpretations of the OT are generally wrong and based in pro-Christian bias. Ancient Jewish interpretation of their own scripture are generally very different from Christian reinterpretations. So NT Christian reinterpretations do not really offer any solid support in the first place.

The “authority to ‘bind and loose’ ” is really a license to innovate and fabricate new and manmade traditions and practices in Christian religion. This “authority” can be argued effectively against depending on other evidence and ones own interpretation of the verses in question.

The claim that sūrat al-Baqarah 2:63, sūrat al-Baqarah 2:93, and sūrat an-Nisā’ 4:154 refer to the same event that the Rabbi refers to is an interesting claim, but I don’t think that there is any hard evidence of this. In other words, “maybe so, maybe not.”

The fact that a random text from the Talmud makes use of a verse from Exodus that in turn refers to Esther and Purim and that somehow justifies Ash Wednesday seems to be a flimsy leap to conclusions on the part of Dennis.

Again he leaps to conclusions by attempting to link verses in Ezekiel to the ash crucifix that modern day priests mark the foreheads of Christian faithful with, and then further imagining that the mark is related to the last letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Even if the same letter was written as a cross in ancient Phoenician there is no unquestionable evidence that indicates that a cross was the mark that was used by ancient Jews to mark foreheads. The mark could have been any of the other actual Hebrew letters, or it could have been any of a wide variety of shapes, a circle, a horizontal line, or a even a crescent, or…. etc. etc. etc. Once again all we are really left with is Dennis Giron’s expert ability at making intelligent guesses.

In regard to the Passover seder, suffice it to say that it’s not called the Quartrodeciman “controversy” for nothing. Again it seems that there is nothing in Christianity that is straightforward and clear.

Thank Almighty God Allah (sws) for the clear guidance that we have in Islam.

LikeLike

Now I will wait for Dennis to obsessively pick my comment apart line by line as he usually does in order to try and save his own conjecture.

LikeLike

The most funniest thing about those Roman Catholics who have Ash Wednesday is that most of them do not believe they shall return to ash or dust when they die. Most of them believe in going to heaven or going to torture places as purgatory and hell.

LikeLike